Human beings can be truly abominable creatures. As if you need to be convinced or reminded of that let me tell you the story behind the Amna Suraka (Red Security) Museum in Sulaymaniyah, northern Iraq. The museum is housed in a former Baathist intelligence headquarters and prison and it is here where Saddam Hussein’s henchmen locked up, tortured and executed thousands of Kurds between 1979 and 1991.

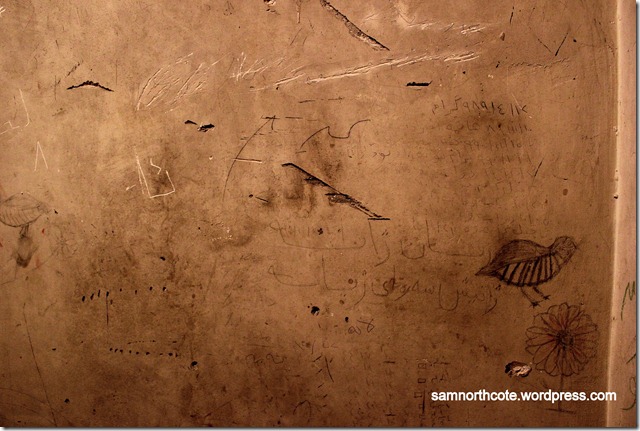

There were very few visitors when I went. My guide led me down tomb-like corridors untouched by natural light and into solitary confinement cells, barred enclosures and interrogation/torture chambers. All the cell walls were etched with graffiti, including some poignant sketches of flowers and birds by a famous dissident Kurdish writer who was interned there.

The prison was horrifically overcrowded when it was in use. According to my guide, up to a hundred prisoners could be crammed into a cage barely big enough for twenty.

I noticed that the floors of these cages, and of the solitary confinement cells, had little mounds of blankets scattered over them. Apparently these blankets had been discarded by the prisoners when they were liberated by Kurdish rebel fighters who attacked and took over the prison in 1991.

The Kurdish rebels who stormed the prison were part of the Peshmerga, a resistance movement whose name translates into English as ‘The Ones Who Face Death’. A badass name I think you’ll agree, and a well-deserved one at that. The Peshmerga started to appear in the 1920s to push for an independent state for the Kurdish people following the collapse of the Ottoman empire. And for most of the 20th Century they bedevilled successive Baghdad-based governments with a tenacious campaign of guerrilla warfare. Later in my trip I would hitch a ride with a member of the Peshmerga in the city of Erbil, but I will get to that in good time.

At the Amna Suraka Museum all the buildings still bear the scars of the standoff between Peshmerga and Iraqi forces. The concrete walls are peppered with bullet holes and mortar impacts. The main courtyard is full of rusting Iraqi tanks and other bits of military hardware – antiaircraft guns, artillery pieces, mortar tubes.

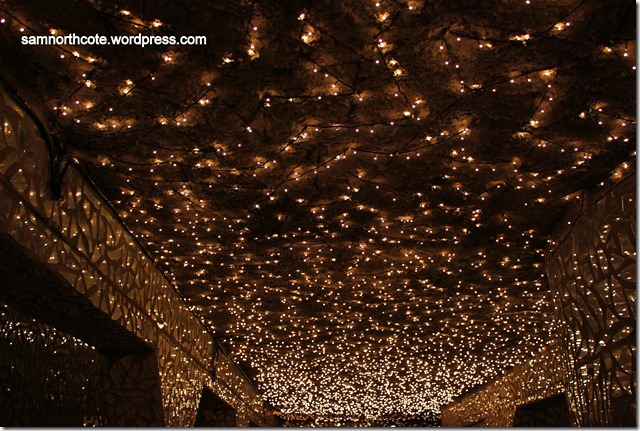

Signs of violence and horror are everywhere. But the first room I entered brought home the magnitude of human suffering under the Baathist government. Suddenly it became abundantly clear why the rebels had fought so relentlessly against the Iraqi army, even though it meant they had to live in cold mountain caves and fight a more well-equipped and numerous enemy without consistent allies to help them. The room my guide had led me into was a hall of mirrors. Thousands of tiny LED lights embedded in the ceiling provided the only source of light and the walls were covered with broken shards of reflective glass.

This room is a memorial to victims of Anfal, a campaign of genocide against the Kurds which Saddam carried out between 1987 and 1988. My guide pointed out that each piece of broken mirror glass represents a life lost during this period of ethnic cleansing, and each one of the tiny lights in the ceiling represents an entire village that was destroyed. The imagery is powerful and makes the numbers more real – 182,000 people murdered and 5,000 villages annihilated – numbers which are otherwise too vast for my feeble mind to compute.

Apparently Saddam named his campaign of mass-murder after the eighth sura (chapter) of the Quran, Al-Anfal, which means ‘the spoils of war’. This name reflects the fact that all Kurdish property was up for grabs. Iraqi troops were instructed to help themselves to any cattle, sheep, goats, money or weapons belonging to the Kurdish people. Even Kurdish women could legitimately be carried off like chattel. Saddam appointed his notorious cousin Ali Hassan al-Majid (more widely known by his grim nickname Chemical Ali) to oversee the methodical pillaging and extermination of Kurdish families. And Ali enthusiastically applied himself to this macabre project – turning villages into corpse landfills.

Kurdish males of militant age were primary targets for the Iraqi soldiers. And anyone suspected of siding with the Peshmerga resistance movement was locked up in prisons like Amna Suraka. No one knows exactly how many people were incarcerated in Amna Suraka because the prison authorities didn’t bother to keep records but it has been estimated that 700 were executed there in just one year.

I was shown sound-proofed interrogation rooms where the Baathists extracted information from suspected rebels by hanging them from the ceiling and electrocuting them in the genitals and other sensitive areas. I was shown a room where guards tortured prisoners by caning them across the soles of their feet. And the place where prisoners were handcuffed in the hallway after a torture session to be kicked and abused by passing guards.

The museum curators have used sculptures to give an impression of what life was like for the prisoners of Amna Suraka. One of the most emotive ones depicted a mother and daughter holding each other and gazing longingly out of the bars of their cell. The guide told me that the child memorialised by this sculpture was born in that very cell.

Finally we went down into a basement area which contained a photo exhibition of Chemical Ali’s attack on the city of Halabja. It was this attack which earned Ali his infamous sobriquet. On March 16th, 1988, as the Iran-Iraq war was coming to an end, he ordered the Iraqi Air Force to bombard the city with chemical bombs, including mustard gas, nerve gas and hydrogen cyanide. This was his way of dealing with the fact that the Peshmerga had captured Halabja with the support of Iran Revolutionary Guards. The result was that 3,200-5,000 people were killed and 7,000-10,000 were injured within just a few hours. But the true extent of the devastation only became clear in the years after the attack when thousands more died of diseases and birth defects as a result of chemical poisoning. Those who survived suffer from a range of medical disorders such as miscarriages, infertility and different forms of cancer.

The day after seeing these horrors from Iraqi Kurdistan’s recent history (more photos available in the gallery above) I went with my friend Ciprian to see a potent symbol of its hopeful future – the University of Suleimani, where Ciprian teaches classical music and basic Italian.

We took a taxi to the brand-new campus (completed just last year, I heard) in which the College of Fine Arts is located. The campus is on the outskirts of Sulaymaniyah and from the main gate the horizon is dominated by snow-capped mountains. Those same mountains where Peshmerga forces once took refuge from the Iraqi army. And the same mountains which are so integral to Kurdish identity. There is a popular saying among the Kurds: ‘Our only friends are the mountains’.

The buildings on the campus are modern and their brightly-lit corridors are lined with stunning works of art. I inspected the paintings closely and was surprised to see that the overwhelming majority of them were highly evocative statements advocating the social and political emancipation of women. We in the West tend to think of Islamic cultures as being very oppressive towards women but, as exemplified by those paintings, Kurdistan is actually quite a liberal society – certainly much more liberal than I expected.

I can’t think of a starker contrast to the hallways of Amna Suraka than the corridors of Suleimani University’s new campus. Students were chatting, laughing and fetching soft-drinks from the canteen. A violinist was standing outside a classroom practising. The ethereal notes of the violin travelled through all the hallways.

I sat and watched as Ciprian tutored a few of his students. The room was small and empty save for an upright piano. The first student of the day was a quietly confident girl who moved gracefully and sang like an angel. I hardly said a word for what could have been hours for all I know. I just sat and listened while the soaring notes of Madama Butterfly filled the room. I learned later that this girl is a famous folk singer in the region and pictures of her can be found all over the bazaars.

The next student was a girl who practised so hard that her teachers have to repeatedly tell her to not sing so much. When she’s not preparing for exams she sings for various musical groups around the city. At the time I met her she was just a week or two away from an exam and she was suffering from a sore throat due to the overuse of her vocal chords. Ciprian had brought a jar of pure New Zealand honey for her to help soothe her throat.

I reflected momentarily on the strangeness of the situation. A Romanian guy teaching Kurdish girls how to sing Italian opera. This brought a smile to my face. And I discovered later that the dean of the College of Fine Arts is a Japanese lady.

Ciprian has had his fair share of frustrations with the university, however. The management have not yet honoured their promise to pay him a salary. The music department is poorly equipped and lacks even basic musical texts. And his students are sometimes wayward, particularly those who are already successful artists.

One of his students, a guy called Mustafa, does not practise when instructed to do so and often turns up to class without notes. He has a great musical talent but is a bit of a maverick. He skips classes to see his girlfriend or to go downtown with his friends to smoke hookah. He’s a friendly guy but a bit of a headache as a pupil.

That being said Ciprian clearly loves being a music teacher. He excels at it and takes pride in his students. And rightly so. Music, I think, is by far the purest thing that we humans have. It is a divine gift, almost unwieldy in the hands of our broken and brutish species. Yet, paradoxically, it is rendered even more beautiful when it comes from the hearts of those who have suffered greatly. Ciprian’s students had lived through the hell of Anfal. Ciprian himself had endured the evils of Ceaușescu’s regime in Romania. A person’s dignity can be destroyed, but there is a dignity in music which can never be killed.

That same afternoon Kak Amanj invited Ciprian and myself to come and talk to the students at the all-girls high school where he teaches. He drove us to the school and showed us around while we waited for his students to come out of an exam. First of all we sat for a while in the headmaster’s office and chatted with the teachers who were gathered there. They were busy going over exam papers but nonetheless they spoke with us.

One of the English teachers was a little flustered. He felt it necessary to apologise on behalf of himself and his colleagues for the quality of their spoken English. ‘We have never had a native English speaker visiting our school before. We feel embarrassed to speak to you. Our English is good enough to teach the students here but to you it must seem very poor.’ Another of the teachers was trying to apply for a post-graduate degree at the University of Southampton and asked if I could help her.

Kak Amanj gave us a tour of the school premises. He pointed out some wall-hangings which his students had made. There were profiles of famous English writers like Charles Dickens and TS Eliot alongside Kurdish poets. There was an essay about the American TV show Prison Break (Kak Amanj’s favourite show). And there was a photo-collage of various Muslim holy sites and religious artefacts. In the middle of the latter poster there was a picture of pilgrims surging around the Kaaba, the black cuboid building in the middle of the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Kak Amanj explained the other photos in the collage: ‘This is cave where prophet received revelation from angel Gabriel. This is prophet’s sandal. This is hair of prophet. This is prophet’s brother-in-law’s house.’

Kak Amanj is deeply religious. One evening I visited him in his room and his TV was tuned into a channel which provides twenty-four-hour live footage of pilgrims performing the Haj at Mecca. Kak Amanj himself completed the Haj just last June. He eagerly described it to me over a cup of hot milk sweetened with honeycomb which his cousins had harvested from a cave with their bare hands. ‘When you touch the Black Stone (the eastern cornerstone of the Kaaba) you forget about everything except God,’ he said, ‘the only thought in your head at that time is God.’

Eventually the students came out of their exam and Kak Amanj gathered them into a classroom to speak to us. ‘They are so shy!’ Kak Amanj said. ‘I’m trying to get them to overcome their shyness.’ But the girls were far from shy. They introduced themselves in almost flawless English and asked us numerous questions.

I was surprised to learn that several of the girls were obsessed with Korean culture and dreamed of living in Korea. It turns out K-pop is extremely popular in Kurdistan and it is usual to see Korean soap operas playing on TV sets in public venues. I’m not sure why but the Kurds feel a strong affinity with the characters in Korean TV dramas.

The students were also fans of British boy bands, especially One Direction and Blue. I asked them if they liked Justin Bieber but they shook their heads vehemently. For some reason they had the idea that Bieber is Jewish and for that reason they disliked him. ‘I’m pretty sure he’s Canadian,’ I said, but they weren’t convinced.

The girl on the far right of the above picture seemed especially eager to talk to me. ‘I’m glad you’re here,’ she said, ‘we have never had a native English speaker to practise our English with before. Thank you for coming to see us.’ She told me her ambition is to be a journalist. ‘I will go anywhere. Syria, Iran, anywhere. I’m not afraid to go to dangerous places to report on them.’

Later Kak Amanj told me that this girl’s father had been killed in the civil war of 2006-2008. On top of that her mother is mentally impaired and relies on her daughters to look after her. She’s an incredibly intelligent girl – I could tell that from just talking to her for a few minutes – but she has very few opportunities to reach her academic potential, balancing studies with looking after her mother. She claimed that she had only slept for eight hours in the last few days. I also learned from Kak Amanj that an American NGO had offered to help her study in the US but for some reason the arrangement fell through.

Kak Amanj was in the process of putting together a dramatization of Great Expectations using some of his students. The play was to be performed at a local theatre in front of other students of the school and parents. Ciprian had agreed to help direct it but as Kak Amanj described his plans it became clear that there was a long way to go before anything resembling a play would come to fruition. Ciprian was slightly worried about this, knowing that his friend Kak Amanj can be a little too laid back when it comes to scheduling things.

Before leaving the school the girls asked Ciprian and myself for our Facebook addresses. They invited us to come and talk to them again and then they all went off to study for their next exam.

In the next and final instalment of this series I take the bus with Ciprian to Erbil via Kirkuk and several military checkpoints. Erbil is an ancient city which is developing fast and is even being touted as ‘the new Dubai’. You can read Part 4 here.

I would like to say a big thank you to everyone who has been reading these posts and commenting on them. I have been overwhelmed by the volume of positive responses. Peace be upon you all, and Godspeed you.

If you found this blog post interesting you might enjoy the content on my new site The Diaspora where I take an in-depth look at places and the characters I meet on my travels.

Such great writing…reporting. This is the best thing I’ve read all day. Thank you.

That’s a very generous compliment. Thank you.

Such a fascinating read every time, thank you.

Thanks for taking the time to read these posts 🙂 Glad you’re enjoying them so far.

Your writing captured the world you have witnessed beautifully. Not only do you give a vivid description, but you manage to describe the recent despair of the region while also highlighting the hope for the future. I will be waiting with bated breath for the final installment. Thank you for bringing this to us.

Many thanks. I tried to capture those two sides to life in Kurdistan – despair and hope – so it’s good to know it came across.

[…] and why I spend so much time on them. It was about that point in my thought process that I read this, the third installment in a blog series about the author, Sam Northcote’s, travels through […]

These posts on Kurdistan are absolute gems.

Congrats on the Freshly Pressed! Very well-deserved.

I’m honoured to receive such a compliment from such a great writer as yourself. Thank you!

Amazing sights and insights. You are so right—human beings can be abominable. Thank you for sharing. I continue to be intrigued by your travels. I’d like to say I want to live vicariously through you, but I no longer believe that that is possible. To be in a place is so much more powerful than to see pictures. But your words *do* help to bridge the gap.

Thanks. I agree with you. There is no substitute for experiencing something first-hand. But if I can just give a glimpse of what life is like in the places I visit then I feel like I’ve achieved what I set out to do.

Your posts on Kurdistan are so fascinating, I am really enjoying reading them and learning about a part of the world that I don’t know much about. Out of the whole post, one of the things that stuck out to me was the Justin Bieber comment. There is much good happening at that school, but it’s sad that even in a place of higher learning, there is still so much ethnic hatred.

Thanks. Yeah, it’s sad that prejudices are so deeply ingrained. It is interesting that education does not necessarily eradicate prejudice. I have met plenty of very intelligent people, including the girls in that high school in Kurdistan, who express racist views worthy of uneducated simpletons.

[…] I mentioned in the previous post, the Peshmerga started out as rebel fighters struggling to obtain autonomy for the Kurdish people. […]

I just visited this Museum today. you have written very well. thanks.

[…] You can read Part 3 of this series here. […]